Macronutrient Metabolic Pathways

Detailed technical explanation of metabolic fates of protein, carbohydrate, and fat processing in research contexts.

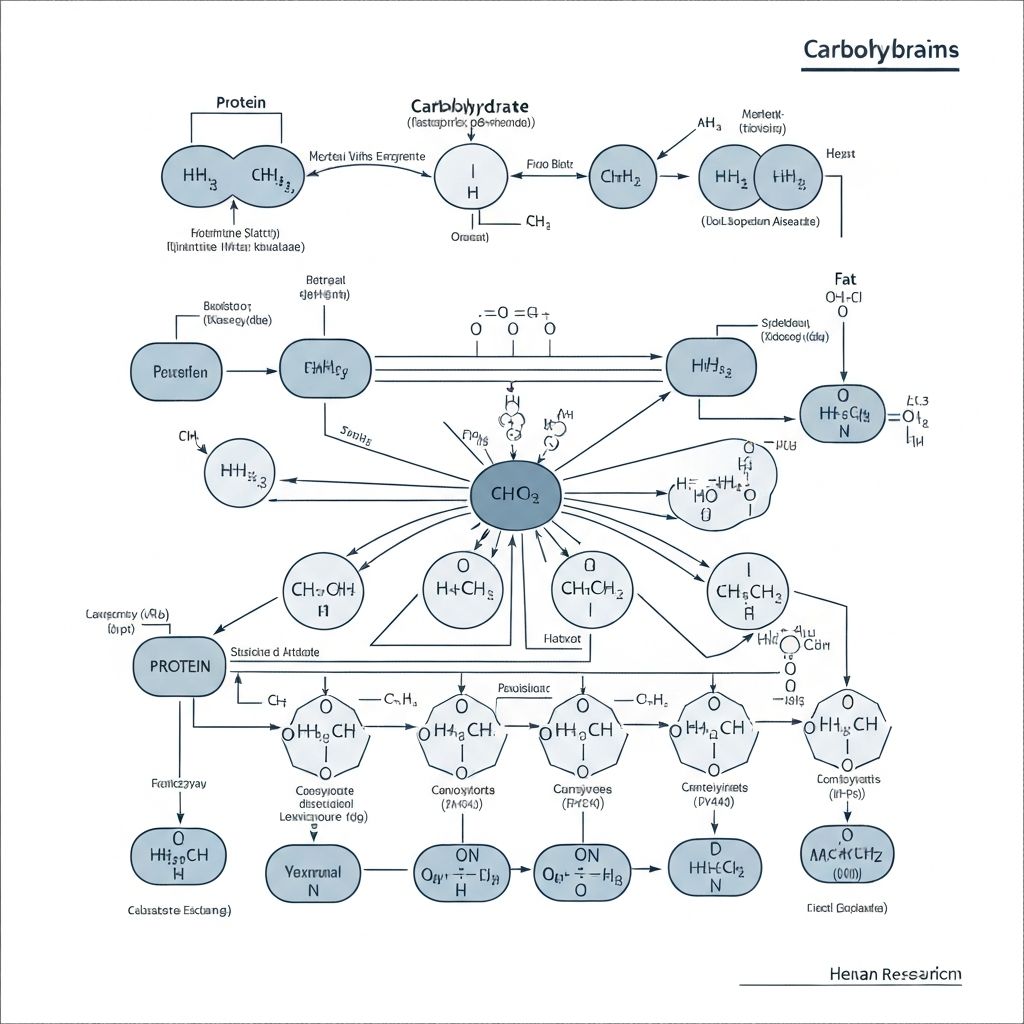

Each macronutrient follows distinct metabolic pathways after ingestion. Understanding these pathways provides technical context for how nutrients are processed and utilized by the body.

Protein Metabolism Pathways

Dietary protein is hydrolyzed into amino acids during digestion. Amino acids enter the bloodstream and are distributed to tissues. In muscle and other tissues, amino acids are incorporated into new protein through ribosomal synthesis. Some amino acids are oxidized for energy through transamination and oxidative deamination. The carbon skeletons can enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle for energy or be converted to glucose through gluconeogenesis or to fatty acids through lipogenesis. Protein synthesis is dynamically balanced with protein breakdown (proteolysis) to maintain tissue protein pools.

Carbohydrate Metabolism Pathways

Dietary carbohydrates are broken down into glucose during digestion. Glucose enters the bloodstream and is taken up by tissues. In glycolysis, glucose is converted to pyruvate, which can enter the tricarboxylic acid cycle for energy production or be converted to fatty acids (de novo lipogenesis). Glucose can also be stored as glycogen in muscle and liver tissues. When metabolic energy is needed, glycogen is mobilized and glucose is produced through glycogenolysis. Glucose can also be synthesized from non-carbohydrate sources through gluconeogenesis.

Fat Metabolism Pathways

Dietary fat is hydrolyzed into fatty acids and glycerol during digestion. These are absorbed and packaged into triglycerides within the intestinal epithelium. Triglycerides are transported to tissues via lipoproteins. In adipose tissue, triglycerides are stored in lipid droplets. During energy deficit states, stored triglycerides are mobilized through lipolysis into fatty acids and glycerol. Fatty acids undergo beta-oxidation to produce acetyl-CoA, which enters the tricarboxylic acid cycle for energy production. The efficiency of fat oxidation depends on metabolic state and energy demands.

Metabolic Integration

These pathways do not operate in isolation but are coordinated through hormonal signals and energy status sensing. Fed state hormones (insulin) promote nutrient storage pathways. Fasted state hormones (glucagon, cortisol) promote nutrient mobilization pathways. The body flexibly switches between pathways depending on energy balance and tissue requirements, creating metabolic flexibility.

Energy Yield Differences

Protein and carbohydrate yield approximately 4 kilocalories per gram through oxidation. Fat yields approximately 9 kilocalories per gram through oxidation. The higher energy density of fat influences its preferential storage in energy-replete states. The thermic effect of different macronutrients varies, with protein having the highest thermic effect (20-30% of ingested energy), followed by carbohydrate (5-10%) and fat (0-3%).

Metabolic Flexibility

The capacity to shift between oxidizing different macronutrients depending on availability is termed metabolic flexibility. In carbohydrate-abundant states, carbohydrate oxidation predominates. In fat-abundant states or during prolonged fasting, fat oxidation increases. This flexibility allows the body to utilize available nutrient sources efficiently.

Educational Context

This article provides technical explanations of metabolic pathways from biochemistry and physiology research. It is educational and does not suggest that manipulation of specific pathways is a strategy for body composition change. Metabolic pathways are complex and tightly regulated. Individual metabolism varies substantially. Consult healthcare professionals for personal guidance.